It’s no secret that we believe spending too much on a monthly car payment is one of the worst things you can possibly do with your hard earned money. For millions of people this takes the form of leasing a car, buying a new car every few years or just buying an expensive car they can’t really afford. We discussed this topic in our Financial Rules as well as the A Lifetime of Financial Advice in Your Wallet article and we really want to delve into it further here.

It’s no secret that we believe spending too much on a monthly car payment is one of the worst things you can possibly do with your hard earned money. For millions of people this takes the form of leasing a car, buying a new car every few years or just buying an expensive car they can’t really afford. We discussed this topic in our Financial Rules as well as the A Lifetime of Financial Advice in Your Wallet article and we really want to delve into it further here.

Many people lease their cars or “manage their payments” on owned cards so they trade in for a new car every few years. They just take their car equity and roll it into the next car to ensure they continue on with the same monthly payment. They view this as a positive thing, but it just means they are continually making a car payment, month after month, as years roll into decades.

They justify this behavior because the monthly payment is manageable, they’ve always had a car payment, or they simply want a new car for whatever reason (vanity, perceived safety, worry about a breakdown, maintenance, etc.).

I haven’t made a car payment since 2007 and my wife hasn’t made one since 2010, so for us not having a car payment is a way of life. I have a 2003 Honda Civic and Laura has a 2003 Toyota Highlander and we each expect to own these cars another 10 years with no monthly payments.

I could go into all the reasons why I dislike spending money on cars and especially expensive cars (they all get you to the same place, right?), but instead let’s just look at the financial ramifications over a 45-year working lifetime (age 22-67):

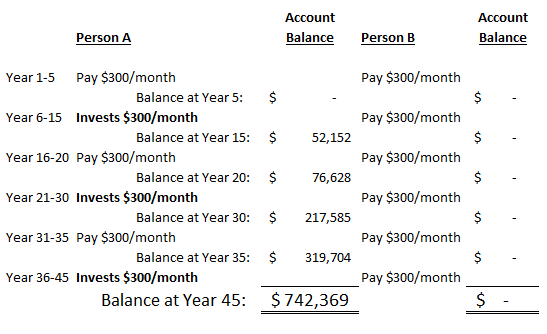

On the heels of our The Miracle of Compound Interest article, this calculation shows how much compounding will amplify your savings if you buy a car with a 5-year loan term and keep driving it for 10 years after your loan is paid off (Years 6-15) and then repeat that cycle twice more over a 45-year working lifetime as compared with someone who leases or manages their payments and makes the same car payment every month for the 45-year period.

In this example Person A will buy a car on Day 1, they will make a $300 monthly payment for a 5-year loan term, then the next 10 years they will save that $300 per month that would have otherwise been spent on a car payment. They’ll repeat this cycle twice more so they’ll buy a new car on the first day of Years 16 and 31. They are paying $300 a month for 15 of the 45 years and they have no car payment for the other 30 years.

Person B will pay what most people consider is a fairly modest $300 per month in ‘managed’ car payments throughout the 45-year span.

Assumptions:

- All monthly car payments will be $300 for Person A and B

- The cars held for 15-years will have no residual value

- All savings will be invested in a low cost mutual fund with an anticipated 8% annual return

The big question is: How much will Person A have sitting in their investment account when they are 67 years old just based off money they saved by not making the extra car payments?

You know for sure that Person A will have made 30 years worth of fewer payments. So they’ll at a minimum have $108,000 ($300 x 12 months x 30 years = $108,000) sitting in their investment account while Person B will have absolutely nothing. But let’s look at the magic of compounding at work here in this chart:

Person A ends up with $742,369 as compared with a whopping $0 for Person B! This wealth accumulation was made possible by Person A simply not buying into the hype of “needing” a new car every few years.

So the next time you hear someone say, “Oh, it’s only a few hundred dollars a month for my car payment, I can afford that,” I hope you show them this article so they understand how much it really adds up to over a lifetime!

Other Examples:

The above example assumes a fairly modest $300 per month car payment (about a $17,000 car with a small interest component) for Person B. If Person B spending more than that per month (and we assume Person A saves the additional amount per month) that just further increases the investment account balance Person A will have at year 45.

I decided to run the same numbers assuming Person A sticks with the same modest car with a $300 monthly payment for their three new cars over 45 years and Person B decides to splurge on a lower level BMW 3-series that runs them $600 per month in managed payments. Person A saves $600 per month in the non-payment months and $300 per month during the 15 years he is making payments (the sum of this spending and saving is the amount Person B is spending each month). Person A winds up with over $2.1 million at the end of the 45-year period!

I ran the same theoretical example but had Person B excessively splurging on a $50,000 BMW 5-series that costs them $900 per month in managed payments. Person A winds up with over $3.5 million at the end of this period!

I know people who own these types of cars and they of course claim they can “afford” them, but do you think they have any clue they are costing themselves millions of dollars? How many extra years are they working just to drive around in a “nice” car?

Notes:

We didn’t take maintenance into account here for Person A, and that’s certainly a consideration. Our cars have needed such little maintenance over the first 10 years of ownership that it’s hard for us to estimate a monthly or yearly figure to include in the above calculation, therefore we omitted it. If you feel it’s necessary to include in the above, you can reduce the $742k, but the larger point certainly holds.

This assumes a new car is purchased by Person A each time. We bought Laura’s Highlander used from Carmax for literally 50% of what we were going to pay for a new car of the same make and model. Buying used would clearly raise the investment balance over 45 years as it would cut at least in half the amount paid during the 15 years of car payments, all of which would be saved.

Richmond Savers has partnered with CardRatings for our coverage of credit card products. Richmond Savers and CardRatings may receive a commission from card issuers.